PHILIPPE BOLTON

HANDMADE RECORDERS & FLAGEOLETS

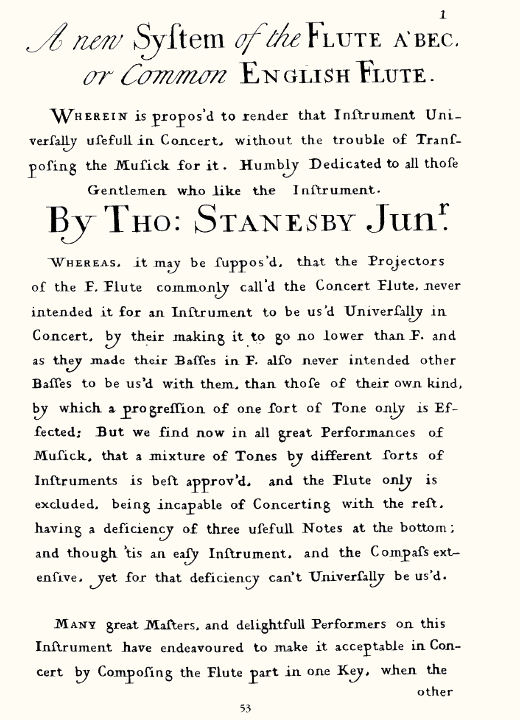

Stanesby Junior's "True Concert Flute"

In 1732 the recorder was probably already on the decline and being progressively replaced by its rival, the German or traverse flute. Since the end of the 17th century the solo or concert recorder was principally the alto (or treble) in f, whose use seems to have been particularty widespread in England. When the recorder was used together with other instruments it was common practice to tranpose its part into a key that suited its range. This seems to have been first done around 1710 by two renowned musicians, Woodcock and Bell, but they did not succeed in having the recorder generally accepted for playing together with other instruments.

The tenor recorder itself was of course no novelty, since it had already existed in the Renaissance, but with a completely different musical

function. Tenor recorders were also made during the baroque period by the Hotteterres in France, Denner in Germany, Bressan,

and Stanesby himself in London. But the idea of using the instrument in this way seems to have been completely new.

To give more emphasis to his argument, Thomas Stanesby built a tenor recorder with a completely different appearance from the tradional recorder

shape. It was made in four parts, with a separate joint for each hand, and a foot ressembling that of the flute.

This new recorder had a definitely solo character. Its wide bore gave it a beautiful tone quality, with a powerful low register and pure high notes, reminiscent of that of the baroque flute. Its foot was bored with a

double hole giving an easy c#. Very few recorders had double holes during the baroque period. Stanesby bored both holes to make them meet and form one single hole inside.

There is at least one original of this magnificent recorder, which is today in the Musée de la Musique, in Paris.

|

Around 1735 the French musician Lewis Merci, established in London, published some solos for the new instrument, but this was insufficient to change the course of events.

The growing popularity of the flute unfortunately prevented Stanesby's invention from taking, and his initiative ended up as a failure.

However we still have one example of this wonderful instrument, which could have saved the recorder from oblivion for a long time. |

In the Encyclopaedia Perthensis Or Universal Dictionary of the Arts, Sciences, Literature, &c, published in Edinburgh en 1816, can be read the following statement:

"The English flutes made by the younger Stanesby came the nearest of any to perfection".

The insinuation at the end of Stanesby's text that recorder players might be unwilling to learn new fingerings could suggest that the recorder had mainly become an instrument for amateurs at that time in England.

|

You can listen to a copy of this instrument here |