PHILIPPE BOLTON

HANDMADE RECORDERS & FLAGEOLETS

HOW RECORDERS WORK

THE MOUTHPIECE

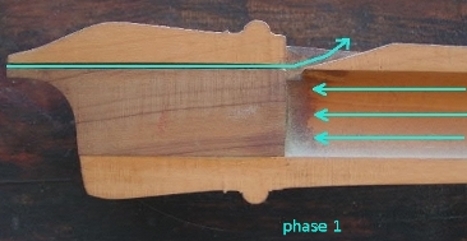

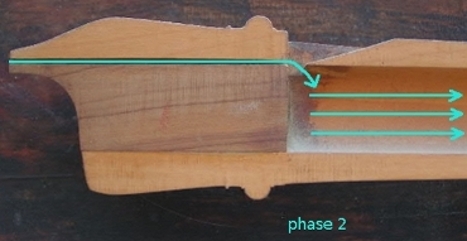

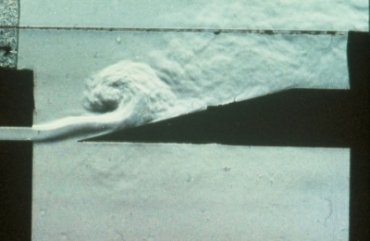

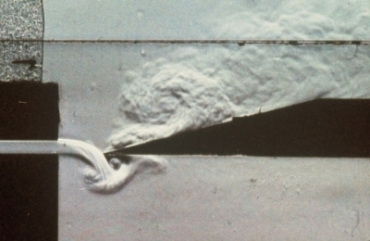

The air jet coming out of the windway interacts with the air column in the instrument's bore and oscillates around the edge or labium, as shown in the pictures below.

|

|

|

| The interaction between the windway and the recorder's air column | The air jet oscillating around the edge of the labium. (Photos : Univesity of Eindhoven, Netherlands) |

Click here for videos corresponding to the pictures above.

There is more information on the air jet in a text by A. Hirschberg (in Dutch) with a diagram & videos.

Click here for a closer view of the recorder's windway

THE RECORDER'S AIR COLUMN

The air molecules inside a wind intrument are comparable to a string of pendulums touching each other. When the first one receives an impulse it passes it on the the next one, and so on until it reaches the end. The last one bounces and sends it back in the opposite direction, then the cycle begins again as shown here:

The column of air inside the recorder is triggered off by the oscillation of the airstram above and below the labium. It vibrates lengthwise and works in the following manner:

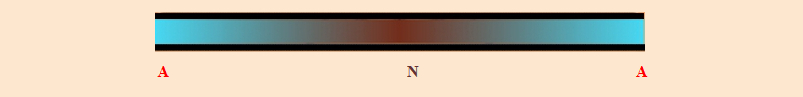

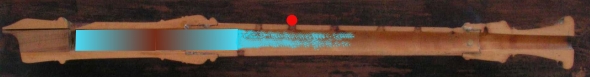

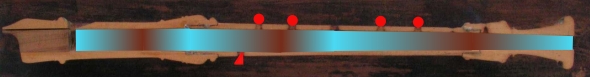

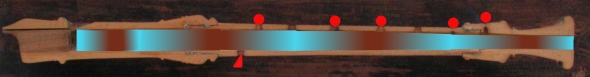

A velocity antinode (A), a zone with maximum movement and minimum pressure (light blue in the following pictures), forms at each end and a velocity node (N), a high pressure zone with no movement (brown in the pictures), forms in the middle.

This system also has other vibrating modes in which it divides itself into two, three, four parts or more, as explained lower down.

This video shows how the air column vibrates. The waves that travel lengthwise along the bore of the instrument, meet at the node and bounce back at the end, then bounce back again on reaching the other end. They keep on moving up and down in this way as long as the player keeps blowing into the instrument.

The air column has several vibrating modes. These are called the registers and correspond to

the partials (or harmonics) which are all present at the same time and give the instrument its tone colour.

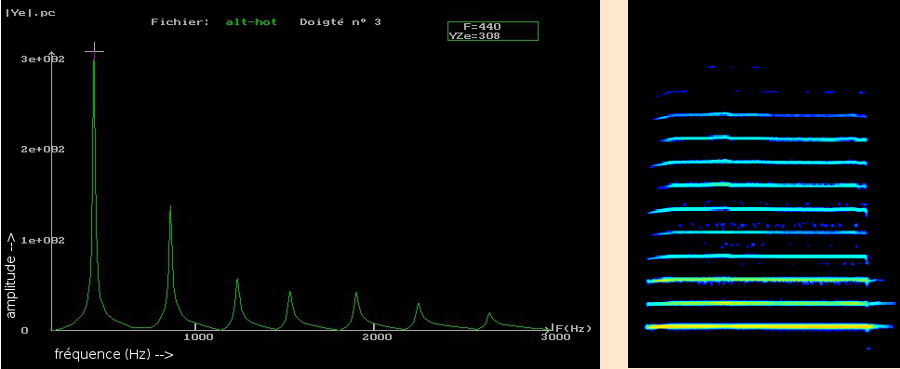

The graph below left reveals the sound spectrum of the 3rd fingering (low a) of a baroque alto or treble recoprder. It shows the frequency and amplitude of the different partials,

each represented by one peak. The first one on the left is dominant. This is the note that we can hear, the fundamental. The others enrich it and caracterise its timbre.

The spectogram on the right gives a real-time visual representation of the different frequencies (the partials) of which this note is made up while it is being played on the same instrument. Each horizontal line represents one partial (or harmonic) starting

from the bottom (the fundamental) upwards. The intensity of each one is shown by its colour. The recorder's timbre analysed in this diagram is a result of the combined influence of the

bore profile and the voicing of the windway.

We use the first four partials for playing notes over a range of two octaves. Below can be found individual information about some of these notes. Click on the pictures below for more detailed information. The note names are for a baroque alto or treble recorder in f.

low f (1st register)

(Click on the picture for more details)

The air column can be shortened by opening holes, giving higher notes, since the vibrating length is shortened. It can of course also be lengthened again by closing holes. If the holes were large enough, opening a hole would be equivalent to cutting the air column completely at that point, but the holes are too small for this, which is why we can use fork fingerings (also called cross fingerings) to play semitones in particular

low a (1st register)

(Click on the picture for more details)

low b (a fork fingering - 1st register)

(Click on the picture for more details)

low d (1st register)

(Click on the picture for more details)

We can thus play over more than an octave up to g (a fork fingering on baroque type recorders)

middle g (a fork fingering - 1st register)

(Click on the picture for more details)

Of course, we can also lengthen the air column again by closing the open holes.

To play higher notes we can inhibit the first register and force the air column to divide into two parts. On the recorder this is done by making the thumb hole

leak. We now have two velocity nodes and each vibrating segment is shorter. This enables us to use the same holes again for other notes.

We are now using the instrument's second register, for which the air column has two velocity nodes.

middle a (2nd register)

(Click on the picture for more details)

By making two leaks (the thumb hole and one on the other side of the instrument), we can inhibit the first two registers and force the air column to divide into three parts, giving notes higher still, using the same holes once more. We are now using the instrument's third register, for which the air column has three velocity nodes.

high e (3rd register)

(Click on the picture for more details)

By making three leaks (the thumb hole and two holes on the top of the instrument) we can inhibit the first three regkisters and force the air column to divide into four parts, giving even higher notes.

We are now using the instrument's fourth register, for which the air column has four velocity nodes.

high g (4th register)

(Click on the picture for more details)

In this way we can play over a range of two octaves and a half (about 30 notes) using only 8 holes. However, the design of the instrument must be correct to enable this.