PHILIPPE BOLTON

HANDMADE RECORDERS & FLAGEOLETS

THE LEFT HAND UPPERMOST ON THE RECORDER?

| Nowadays the recorder is normally played with the left hand above and the right hand below, as shown in the photograph opposite. |

|

However, there is no logical reason for playing with the left hand uppermost as is the rule today. During the middle ages and the Renaissance, instruments were made in such a way that the hands could be placed either way round as was most convenient for each player. The picture on the left is a detail of a 15th century painting showing recorder players. The drawing on the right comes from the title page of Silvestro Ganassi's Fontegara printed during the following century. In both we have inverted hand positions.

|

|

The following three documents suggest that both ways of playing were considered quite normal until about the middle of the seventeenth century.

|

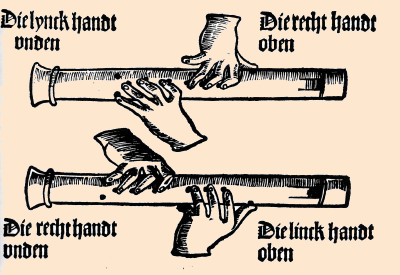

1 - In his treatise "Musica getutscht" (1511), Sebastian Virdung shows us the two ways of placing the hands on the instrument.

|

2 - Pierre Trichet gives us the same indications and a very simiular drawing in his "Traité des instruments" which was written around 1640.

|

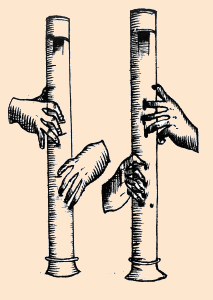

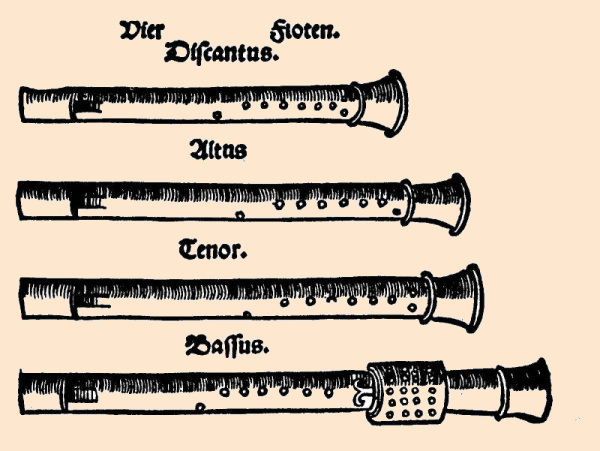

3 - In order to enable playing either way, the bottom hole was usually bored twice, on both sides of the l'instrument. The player would plug the unused hole with wax.

This feature is visible in the pictures above, and on the set of recorders below, drawn by Agricola. The key on the bass recorder could be operated from either side.

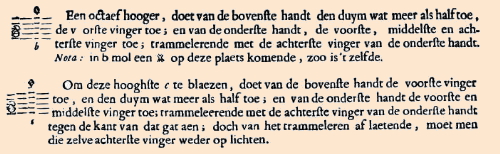

In 1646, in the text bound with van Eyck's Fluyten Lust-Hof describing the recorder's fingerings, Blankenburgh just mentions the hand above (de bovenste handt) and the hand below (de onderste handt).

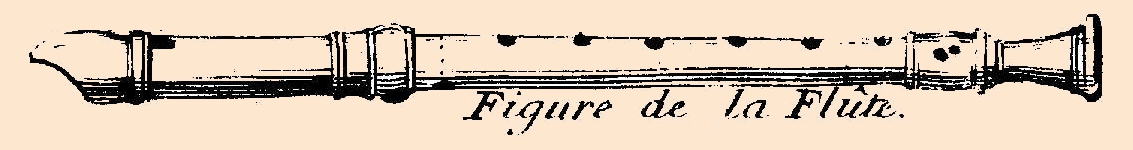

But the drawing of the recorder in this document does not show two bottom holes, so this instrument could only have been played with the left hand above and the right hand underneath.

Playing with the left hand uppermost seems to have become general practice during the baroque period. This is explained in the three following treatises (from left to right, Bismantova, Hotteterre le Romain, Majer.

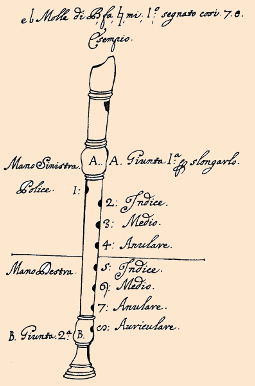

In 1677, in the drawing that goes with his fingering chart, Bartolomeo Bismantova indicates "Mano Sinistra" (left hand), for the one above, and "Mano Destra" (right hand), for the one below. |

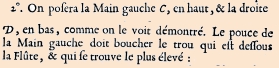

In his "Traité de la Flûte à Bec" (1707) Jacques Hotteterre-le-Romain states: (The left hand (C) is placed above and the right hand (D) below as shown.The thumb of the left hand is to close the uppermost hole which is situated behind the recorder.)

|

In his method published in 1732, Joseph Majer stipulates: "Linker hand" (left hand) for the hand above and "Rechter hand" (right hand) for the one below. |

|

However this was probably just a convention, and makers continued to bore the bottom hole on both sides of instruments whose foot could not be turned to put it on the other side. The two bottom holes are visible on this soprano (descant) recorder, in two parts instead of three, made in the Netherlands by Robert Wijne (1698-1774). The hole for the little finger of the left hand is filled with wax. The drawing on the right by Johann Christoph Weigel (1722) shows a musician playing with his right hand uppermost. |

|

|

Nowadays double holes have made it compulsory to play with the right hand below, because they are bored at an angle, in line with the ring finger and little finger. Moreover, the hole on the left, which is opened alone to play the semitone, is normally smaller than the other one.

Playing the other way round with double holes means having a recorder specially made or adapted for that purpose by an instrument maker. |

This drawing by Hotteterre, printed in his recorder fingering chart, proves that double holes were known in the beginning of the 18th century. The recorder illustrated here could only be played with the right hand underneath.